|

My name is Jim Hance, and I’ll be posting stories to a new Substack, Dancing on the 1. The stories will be about Cajun and zydeco musicians, and dance events, because knowing more about music and the artists who make it will sustain interest in it. Both Cajun and zydeco, for most dancers, are non-technical dances without strict rules except for one caveat: If you're smilin', you're doin' it right. The title of this blog, “Dancing on the 1,” is intended to poke fun at the informality of the dance and to invite you to do your own thing, which of course you will do without invitation. There is ONE hard-and-fast rule that applies to every dance I've ever encountered: whatever dance you do, STAY ON THE BEAT!

Cajun and zydeco music are both products of one area of Southwest Louisiana that has come to be called Acadiana. While under the French occupation of the New World, immigrants came to the area either by force (as slaves) or to claim some independence from oppression. The common language that influenced a separate culture in Acadiana apart from other colonized parts of the New World was French. French-speaking immigrants from Nova Scotia were expelled from Canada when the British seized control, and found they were welcome to settle in Louisiana and became known there as Cajuns. French-speaking blacks formed their own social communities and culture in Acadiana and they commonly identify as Creole. The musical heritages of each continued to evolve independent of the rest of the continent as Cajun and Creole music was insulated by the French spoken there. While over the past century both Cajun and Creole music and cultures have become more influenced by the prevailing American culture of the United States, specific signatures of the Cajun and Creole music remain intact in contemporary Cajun and zydeco music. Cajun music has a fast tempo with an accent on the up beat. Zydeco, with a distinct blues influence, is typically a bit little slower with a heavy emphasis on the down beat, encouraging you to "dance down into the floor.” Whether the beat is up or down, the music will make you want to move! My love for Cajun music started when my wife and I were invited by a friend to a Bon Temps Social Club dance in San Diego in 1994. Their monthly dances featured live music by bands from Louisiana. We were introduced to a whole new activity and acquired a passion for social dancing that started with Cajun dancing, and soon included zydeco, country dancing, Lindy swing, west coast swing, nightclub two-step, waltz, cha cha, salsa, and hustle dancing, to name a few. Over time we expanded our dancing acquaintances from a handful to thousands, many of whom we are still in contact with three decades later. My wife, Jane, became a west coast swing dance instructor, and I became a deejay for Cajun and zydeco dances, and a promoter for Cajun and zydeco dance events. It didn't take long before we strayed from the basics of the dances to making up our own dance stylings. Jane came up with her own dance styling to zydeco music she called "zyde-swing," incorporating Lindy and west coast swing connection and moves in her zydeco. And I have to confess that much of my zydeco dancing is informed by hustle: soft connection, continuous circular motion on the dance floor, and a flow that works particularly well with zydeco infused with funk or disco. This isn't wierd. This is what dancers do. West coast swing at most clubs and studios is danced to the pop music trend of the moment. West coast swing dancers have added hustle, tango, salsa, zouk, Carolina shag, and hip-hop styling to their swing dancing as pop music cycles through music trends. Most west coast swing dancers are okay with any styling you choose to add as long as you stay on beat and, preferably, maintain the anchor step and swing connection somewhere in the amalgamation. This is happening in the Cajun and zydeco dance scenes as well. Some Cajun and zydeco styling looks a bit like Pony that was once one of the dances in national country dance competitions — a lot of styling from jitterbug and east coast swing. Other styling seems to be derived from salsa and hustle, with lots of circular motion on the dance floor, deep drops into the knees and hand tosses added in, Others highlight the zydeco slide with lots of heel swivel action. Others include "swing outs" and underarm turns. If you want to see the diverse variations of Cajun and zydeco being danced in Acadiana, check out the postings of "Fran" to our Florida Cajun and Zydeco Dancers group on Facebook. Now you have permission to play with your zydeco dance and make it your own. We wouldn't want it any other way.

0 Comments

Date: Sunday, July 16

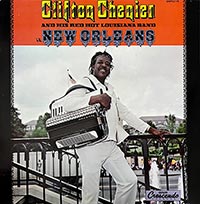

Time: 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. 6140 Braman Place the Village of Citrus Grove Dearest Friends and Music Lovers: Please join us in front of our home where I will be performing with Lisa Haley & the Zydekats GRAMMY Nominees “Americana/Cajun/Zydeco category” “Joyful, exotic… ala the bluesy moans of Janis Joplin…” - Los Angeles Times The most joyful American/Cajun/Zydeco act on tour today! "Prepare to catch “Zydecosis!” This GRAMMY Nominated fiddler, dancer, vocalist & songwriter serves up heart-moving Louisiana Bayou rhythms, traditional stylings and original songs speaking to all ages. These will be a very high energy show with great musicians and great music. Different from what I am used to playing but a lot of fun. Bring your chairs, your wine and enjoy the night with some Louisiana Bayou rhythms. Music cover charge $5 per person paid at the night of event. Please RSVP in event and pass the word around. Thank you hope to see you there. [From Facebook group, Florida Cajun and Zydeco Dancers]  LINER NOTES BY Dave Dexter, Jr. Joel Selvin has described zydeco as “a musical form derived from the wedding of traditional Cajun music of the Louisiana swamplands and blues sounds from all over the south.” And when it comes to zydeco, Clifton Chenier is the master. Not only in Louisiana, but in Texas as well, his powerful voice and his unconventional but intriguing accordion are extremely popular. “Et toi, et toi, et toi,” Chenier yells on the bandstand. “Bon ton roulet — let the good times roll.” And roll they do. Zydeco fans are as demonstrative as little girls at a Donny Osmond concert. Much of that spontaneous, unstaged enthusiasm is apparent on the two sides of this LP, both recorded in New Orleans with Gene Norman in the booth as producer. Chenier and his big Hohner accordion are somewhat incongruous, perhaps, in the blues field. Hohner harmonicas are, of course, common in blues. But Chenier and his formidable squeeze-box provide a unique sound and sight as the 1980s approach — and Clifton’s odd, compelling vocal style adds to the distinctive qualities exhibited by Chenier and his musicians on record as well as on live engagements. A brother, Cleveland Chenier, invariably stands at Clifton’s side “scrubbing” his rubboard, helping propel a peculiar rhythm which receives additional impetus from Paul Senegal’s guitar, Robert Peter’s drums and bass plucked, on this record, by Joe Brouchet or Benny Grunch. John Hart on tenor saxophone completes the Chenier ensemble. Every song on this LP was composed by Clifton Chenier. Some of his compositions carry titles and lyrics in the Cajun patois; others are in conventional English. In the studio, Clifton and his colleagues work quickly. Leader Chenier detests rehearsing and run-downs of songs. “When that red light goes on and the tape is running through the machine,” he told producer Norman, “I want to perform the song just once and go on to the next tune. Let’s not mess around trying to get a better take. The best is the first.” And so, in this collection of Chenieriana, tape splices and other mechanical ploys are at a minimum. Both sides reflect the Chenier group honestly, warts and all. Writing in the Austin Sun in 1974, Joe Gracey philosophised: “Clifton Chenier could have been a folk artist in the pure, isolated, ethnic sense of the word. In the 1920s or the ’40s, his music would have been local and inbred. Effective but limited. He could have remained a ‘folk artist’ by closing his eyes and ears to the music explosions of the ’50s and ’60s. Nobody would have questioned his integrity, or ability, had he continued to play the music of his father into his grave. But Clifton added blues and rhythm ‘n’ blues to his native zydeco repertory… he has drawn on every possible source for inspiration, experimenting and discarding constantly. Clifton is a great blues singer. He injects the blues with intense power. He is never apart from his music. There is no doubt whatsoever that he is just as at home with the blues as he is with zydeco; his music is diverse in content and single-minded in style. He knows what he knows with no excess musical baggage to get in the way.” Discerning, serious blues/jazz buffs — and musicians — will quickly become aware of the odd rhythmic patterns evident on these recorded tracks. They have little to do with Robert Peter’s technique on tubs. Instead, they emanate from Cleveland Chenier’s rubboard — he employs eight beer bottle openers, the kind made with a thin metal rod formed into a handle with a loop. He holds six of them in one hand and two in the other, scraping them all across his corrugated board and producing a rattling, unconventional polyrhythm which gives the Chenier band much of its distinctivness. At times the other musicians take a tacit break while the two brothers perform duet style. Born on a farm outside Opelousas, Louisiana on June 25, 1925, Clifton Chenier learned accordion early, playing waltzes, two-steps, polkas and traditional Acadian melodies as a child. His father, Joseph, was “the best accordion player in the state,” Clifton recalls, but was forced to work in the humid cane and corn fields to support his family. Clifton’s older brother, Cleveland, left the farm in the 1940s to make Lake Charles his home. Clifton followed him in 1946, hoping to become a full-time musician. But it was not to be. So he and his wife moved on to Port Arthur, where Clifton found a job with an oil refinery. But on weekends he played his accordion and sang, leaning heavily on tunes his father had taught him. In time, he attracted enough notoriety to be recorded and quickly he added to his reputation in the Louisiana-Texas area. The Cheniers occasionally work the West Coast, moving about in a van. And they have played Europe. But mainly the combo does its thing in zydeco country, a section of the U.S.A. unique unto itself, bayou country, where French and Cajun patois is as common as English and where the pace is in slow motion. Chenier is a handsome man. He dresses impeccably and speaks with authority. For years he has been featured on an early morning television show directed to rural residents of Cajun country. He is proud of his heritage and confident of his musicianship. He does not object when his fans call him ‘King.’ Sometimes he works with a velvety crown on his head, looking much like the characters in a margarine television commercial. No one can say Clifton is lacking in humor. But it’s his music, he says, for which he lives. Someday, he muses, zydeco may spread to the big cities of the north. Until that happens, Clifton Chenier will continue working every night as he has for more than 20 years. And records like this will be carrying his talents to places he’s never visited. In 1978, Dave Dexter, Jr. was chief copy editor for Billboard Magazine, and author of Playback, published by Billboard Books, New York.  Cajun music is without doubt one of the happiest extrovert forms of dance music heard in this vast and diverse country of ours. The roots of this music reach a long way back to the France of the 16th century and to the Acadia in Canada of the 17th century. French immigrants arrived from Brittany, Normandy, and Picardy to settle in Acadia in 1604. During Queen Anne’s War, the English won control of Acadia in 1713 and the Acadians (or “Cajuns” which is a colloquial shortening) refused to fight for the British against the French, and were forced to leave Canada. The poor Acadians got a cold reception when they arrived in Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Savannah. Many died on the way, but with the hope that they would meet fellow Frenchmen, the survivors pushed on to Louisiana where the first group arrived in 1756. The French and Spanish indeed welcomed the Cajuns and helped them settle in the southwestern part of the state. There they have remained ever since to farm and fish along the bayous. As a result of the Second World War, the draft, the boom in industry, and well paying jobs in cities like Houston and the ship yards on the West Coast, many Cajuns discovered that life on the farms wasn’t what it used to be. Today there are large settlements of them not only in Houston, Bay Town, and Galveston, but also in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay area. The Cajuns have maintained their traditions including their Catholic religion and the French language, but since they were mostly country people with little book learning, and language has been orally transmitted and has undergone considerable change. Today’s patois spoken in southwest Louisiana is perhaps difficult for a modern Parisian to understand, but maybe it’s the Parisian French which has undergone the drastic change! In the late 1920s when the first recordings of Cajun music were made (note list of recordings at end of text), considerable influence from other forms of American music like jazz, pop, and hillbilly music was already in evidence. Yet the purer, older songs and traditions were handed down in many homes, and recent recordings made by Dr. Harry Oster have documented much in the way of songs from the 18th century and earlier. However, the commercial record companies, even in the 20s, were no doubt more interested in the performers who were popular at dances (or fais do dos) and picnics. These recording groups were the ones who would introduce the new outside elements, thus constantly giving the music a new lease on life. Prior to 1930, the early commercial recordings were remarkably traditional and only accordion, fiddle, and sometimes the newly introduced guitar were heard along with the triangle, their rhythm instrument. Then in the 30s the big change came with the influx of southern rural people into Louisiana. With the expanding oil industry the hillbilly influence became very strong. Some like Joe Falcon and the Breaux Brothers tried to keep the old music going, but the most popular recording groups soon were the string bands which were using a fiddle lead, instead of the accordion, along with a bass, and steel guitar. Even the singing was often in English. Young string bands like the Hackberry Ramblers and the Rayne-Bo Ramblers were replacing the accordion players yet retained a very distinct Cajun quality. Towards the end of the 30s, the older accordion music had almost disappeared as far as the records were concerned. Joe Falcon told me that he gave up the accordion and switched to playing drums just to keep playing music. Then after World War II, with young Cajuns returning home and longing for some familiar sounds, they were ready for a wild and carefree fiddler named Harry Choates who had a band in the Western Swing style which was very popular throughout the South, but especially in Louisiana and Texas and among country people all over the U.S. He recorded the favorite “Jole Blonde” for the Gold Star label, and this record became a hit along the Gulf Coast. Other groups went back to playing the older songs and dance steps, and soon a real revival was underway. Nathan Abshire and his accordion was heard weekly over KPLC in Lake Charles, and Joe Falcon, the man who made the very first Cajun records in the 20s, came back with his accordion and played dances until his death in 1965. The recordings on this LP come from this period when the Cajuns rediscovered their joyous music once more. With the addition of string bass, drums, and steel guitars, the music had a wider appeal among the younger generation. Unlike in the 20s and 30s when Cajun music, along with other kinds of “ethnic” music, was recorded by the national labels like Victor, Columbia and Decca, this post war period saw the proliferation of small independent labels that were willing to record almost anything that could be sold. Mr. Khoury is not a Cajun, but he runs a record shop and knew what people wanted to hear. In those days the recordings were mostly made at local radio stations since there were no recording studios between New Orleans and Houston. Some of these recordings are perhaps technically not of the best quality, but I have always felt that it’s not the technical part that counts but the spirit and the feeling of the musicians, and both were undeniably present in generous amounts on these classic performances! — Chris Strachwitz, 1969 May I suggest the following recordings of Cajun music: Folksongs of the Louisiana Acadians recorded in Mamou by Dr. Harry Oster with extensive historic background text about the people and their music. An essential album for anyone interested in Cajun music. Folklyric LP No. 4 (soon to be reissued on the Arhoolie label) Re-issues of early commercial performances by Joe Falcon, Leo Soileau, the Hackberry Ramblers, Lawrence Walker, Miller’s Merry-makers, and many other are available on a series Old Timeky LPs — see catalog. Harry Choates “Jole Blonde” and others, “D” Records LP No. 7000. The Hackberry Ramblers — great fiddle by Luderin Darbone, Arhoolie LP 5003. Iry LeJeune — one of the great accordion players, Goldband LPs 7740 and 7741. American French Music with various artists, Goldband LP 7738. Joseph Falcon recorded “live” at a dance, Arhoolie 5005. Ambrose Thibodeaux traditional Cajun accordion, La Louisiane 112 and 119. Cajun Hits, various fine contemporary groups, Swallow 6001 and 6003. Cajun Fais Do Do with Nathan Abshire and others, Arhoolie 5004 The Balfa Brothers, excellent traditional Cajun music, Swallow 6011. Clifton Chenier, best of the Negro Cajun Zydeco accordion players who mixes Cajun music with blues and R&B, Arhoolie 1024, 1031 and 1038. Zydeco, various Negro performers, a historic survey. Arhoolie 1009. An important book dealing with the Cajun country is Cajun Sketches by Lauren C. Post, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 1962. Dealing with the geography, economics, traditions, and music of the region. Highly recommended. |

Jim HanceStories about Cajun and Zydeco artists and their music. Archives

March 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed