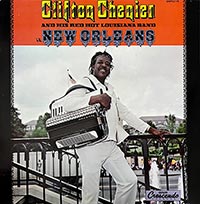

LINER NOTES BY Dave Dexter, Jr. Joel Selvin has described zydeco as “a musical form derived from the wedding of traditional Cajun music of the Louisiana swamplands and blues sounds from all over the south.” And when it comes to zydeco, Clifton Chenier is the master. Not only in Louisiana, but in Texas as well, his powerful voice and his unconventional but intriguing accordion are extremely popular. “Et toi, et toi, et toi,” Chenier yells on the bandstand. “Bon ton roulet — let the good times roll.” And roll they do. Zydeco fans are as demonstrative as little girls at a Donny Osmond concert. Much of that spontaneous, unstaged enthusiasm is apparent on the two sides of this LP, both recorded in New Orleans with Gene Norman in the booth as producer. Chenier and his big Hohner accordion are somewhat incongruous, perhaps, in the blues field. Hohner harmonicas are, of course, common in blues. But Chenier and his formidable squeeze-box provide a unique sound and sight as the 1980s approach — and Clifton’s odd, compelling vocal style adds to the distinctive qualities exhibited by Chenier and his musicians on record as well as on live engagements. A brother, Cleveland Chenier, invariably stands at Clifton’s side “scrubbing” his rubboard, helping propel a peculiar rhythm which receives additional impetus from Paul Senegal’s guitar, Robert Peter’s drums and bass plucked, on this record, by Joe Brouchet or Benny Grunch. John Hart on tenor saxophone completes the Chenier ensemble. Every song on this LP was composed by Clifton Chenier. Some of his compositions carry titles and lyrics in the Cajun patois; others are in conventional English. In the studio, Clifton and his colleagues work quickly. Leader Chenier detests rehearsing and run-downs of songs. “When that red light goes on and the tape is running through the machine,” he told producer Norman, “I want to perform the song just once and go on to the next tune. Let’s not mess around trying to get a better take. The best is the first.” And so, in this collection of Chenieriana, tape splices and other mechanical ploys are at a minimum. Both sides reflect the Chenier group honestly, warts and all. Writing in the Austin Sun in 1974, Joe Gracey philosophised: “Clifton Chenier could have been a folk artist in the pure, isolated, ethnic sense of the word. In the 1920s or the ’40s, his music would have been local and inbred. Effective but limited. He could have remained a ‘folk artist’ by closing his eyes and ears to the music explosions of the ’50s and ’60s. Nobody would have questioned his integrity, or ability, had he continued to play the music of his father into his grave. But Clifton added blues and rhythm ‘n’ blues to his native zydeco repertory… he has drawn on every possible source for inspiration, experimenting and discarding constantly. Clifton is a great blues singer. He injects the blues with intense power. He is never apart from his music. There is no doubt whatsoever that he is just as at home with the blues as he is with zydeco; his music is diverse in content and single-minded in style. He knows what he knows with no excess musical baggage to get in the way.” Discerning, serious blues/jazz buffs — and musicians — will quickly become aware of the odd rhythmic patterns evident on these recorded tracks. They have little to do with Robert Peter’s technique on tubs. Instead, they emanate from Cleveland Chenier’s rubboard — he employs eight beer bottle openers, the kind made with a thin metal rod formed into a handle with a loop. He holds six of them in one hand and two in the other, scraping them all across his corrugated board and producing a rattling, unconventional polyrhythm which gives the Chenier band much of its distinctivness. At times the other musicians take a tacit break while the two brothers perform duet style. Born on a farm outside Opelousas, Louisiana on June 25, 1925, Clifton Chenier learned accordion early, playing waltzes, two-steps, polkas and traditional Acadian melodies as a child. His father, Joseph, was “the best accordion player in the state,” Clifton recalls, but was forced to work in the humid cane and corn fields to support his family. Clifton’s older brother, Cleveland, left the farm in the 1940s to make Lake Charles his home. Clifton followed him in 1946, hoping to become a full-time musician. But it was not to be. So he and his wife moved on to Port Arthur, where Clifton found a job with an oil refinery. But on weekends he played his accordion and sang, leaning heavily on tunes his father had taught him. In time, he attracted enough notoriety to be recorded and quickly he added to his reputation in the Louisiana-Texas area. The Cheniers occasionally work the West Coast, moving about in a van. And they have played Europe. But mainly the combo does its thing in zydeco country, a section of the U.S.A. unique unto itself, bayou country, where French and Cajun patois is as common as English and where the pace is in slow motion. Chenier is a handsome man. He dresses impeccably and speaks with authority. For years he has been featured on an early morning television show directed to rural residents of Cajun country. He is proud of his heritage and confident of his musicianship. He does not object when his fans call him ‘King.’ Sometimes he works with a velvety crown on his head, looking much like the characters in a margarine television commercial. No one can say Clifton is lacking in humor. But it’s his music, he says, for which he lives. Someday, he muses, zydeco may spread to the big cities of the north. Until that happens, Clifton Chenier will continue working every night as he has for more than 20 years. And records like this will be carrying his talents to places he’s never visited. In 1978, Dave Dexter, Jr. was chief copy editor for Billboard Magazine, and author of Playback, published by Billboard Books, New York.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Jim HanceStories about Cajun and Zydeco artists and their music. Archives

March 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed